|

| Agile In Education Compass - designed by Stuart Young (Radtac) |

My brother Marco is a primary school teacher in Italy.

From this

perspective we share a common interest, since I am a trainer and I am

interested in how people learn.

I’ve been actually interested in that for more

than 25 years: as a Scout leader it has been very clear for me that educating boys and girls is giving them the

opportunity to learn and become the best they can be.

It is not

by chance that the verb “to educate” comes from the Latin “ex ducere”, which

literally means “to lead out” what a person already potentially is.

Last year

we happened to talk about how to create a learning experience for primary

school kids which would encompass the following:

- Being more adaptable to a kid’s specific learning needs

- Being a meaningful experience involving feelings and physical emotions

- Fostering self-development and co-education

- Training skills which are crucial in the 21st century and the school is traditionally not that good at teaching, e.g.

- self-organization

- leadership

- ability to plan

- imagination

- self-reflection

- dealing with uncertainties and the unknown

On the

other side, I was aware of the many experiences in the field of Agile in

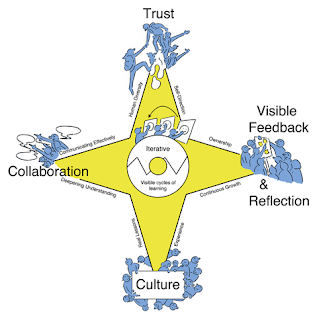

Education, which are summarized on the website agileineducation.org and conceptualized through the Agile Education compass created by a

group of Agile educators at the Scrum Gathering in Orlando in April 2016.

So the

proposal was kind of natural: why not trying a learning experience based on

Agile values and principles? Learning and using the Scrum framework looked to

me the simplest and most straightforward option to help the kids practice

agility at school.

The very

first step was actually to educate Marco in Scrum: I led him through an

introductory session to the Agile manifesto, Scrum and its foundation,

including Empirical Process Control.

This was

enough in catching him up in the idea: the confidence in his older brother did

the rest in accumulating enough enthusiasm and motivation to get going with the

whole experiment J

Basically

we wanted to have a first-hand validation that applying Scrum in a primary

school class is doable, kids enjoy it, they can learn faster and practice

skills they normally do not in a traditional classroom environment.

Below I

will describe the whole concept we adopted, how we structured it, a report of

the different phases and some final results we achieved (I will actually split the whole story over a couple of posts to make each post reasonably short).

Selecting the project

The first

problem to solve was to pick a learning project which was suitable for the

experiment.

It should

have been challenging enough to get a meaningful result out of it.

At the same

time it should have been concrete enough, so that the kids could actually

produce something tangible (iteratively and incrementally) and see the outcome

of their work.

There is no Scrum team without a productJ.

The class

consisted of 19 kids: considering the recommended size of a Scrum team between

3-9 people, the selected learning project should have been suitable to work in

multi-team environment. Multiple Scrum teams had to work in parallel on the

same product and get success by collaborating and integrating their work,

hopefully at each and every iteration.

The natural

choice emerged to be an interdisciplinary geography project, including learning

objectives in arts (mainly image), math (mainly statistics) and humanities.

Students in

the 5th grade are supposed to study the whole Italy and specifically

each of the different 20 regions which form the country. This looked very

promising for creating a backlog of multiple items, which many teams could work

on at the same time: each Product Backlog Item would have been

one of the 20 regions.

Kick-off

The whole

experiment started in the first week of November 2016.

In a previous meeting, Marco had informed all parents about the trial which would have involved their children during the year. He explained them the idea and the rationale and all of them showed curiosity and agreed to move on, based also on the trust they had in the teacher.

The kids were also prepared. They were informed that this year they would have studied geography in a different way: they got full of enthusiasm but also expectations.

In a previous meeting, Marco had informed all parents about the trial which would have involved their children during the year. He explained them the idea and the rationale and all of them showed curiosity and agreed to move on, based also on the trust they had in the teacher.

The kids were also prepared. They were informed that this year they would have studied geography in a different way: they got full of enthusiasm but also expectations.

Whenever I kick-off

one or multiple Scrum teams, I basically help them learn three things:

- Know about the Process

- Know about the Product

- Know about each other

- Deliver an introductory training on Agile and Scrum to all students

- Create and kick-start the different teams

- Getting the teams acquainted with the backlog

- Hold the first Sprint Planning

Marco introduced the day and then we had a 2-hours interactive training so that the kids could understand:

- What is the most suitable approach to solving complex problems, like learning something new

- The Agile values and principles'

- The Scrum roles, events and artifacts

It was just amazing

how they immediately grasped this and made all sense to them.

At the end

of the 2 hours they could explain what a Product Owner or a Sprint is.

After a

short break we moved to their actual classroom where my brother had prepared

all the necessary supply I had

instructed him to buy to facilitate the day and the team work.

So we started

presenting the backlog. To make the final product visual, Marco prepared a

big blank map of Italy, just reporting the borders of the different regions

(see the draft picture below).

Each

backlog item (i.e. representing each of the 20 Italian regions) had to fulfill the

following Acceptance Criteria.

- A construction paper shape of the region must be prepared:

- Borders must conform to the map

- High and low grounds are represented

- Hydrography is represented

- Cities are positioned properly and regional/provincial capitals highlighted

- Different sectors of local economy are represented

- Peculiarities of the region are highlighted

- A report on the whole region must be prepared and shared by the team with the whole class

In that way

the kids had something concrete to produce and an underlying architecture which

made integration easy. At the same time the different teams could work

independently.

Then we

moved to form the Scrum teams: with a class of 19 kids we decided to split them

in three teams. The teacher would have the role of Product Owner and I

would formally act as a Scrum Master for all teams.

However I

knew that I could not be present so I instructed my brother that he

should work as a facilitator as well and take actually care of the

Scrum Mastering part, while I would have coached and consulted him remotely along the

way.

During the

preparation phase we evaluated whether it would be a good idea to

let the kids self-organize in three teams by following a certain number of

constraints, but we discarded the option. Marco did not feel too

comfortable and he wanted to make sure that the groups had enough diversity

from many perspectives, including different learning styles and proficiency at

school, which probably the kids would have not been able to take into the right

consideration themselves.

So we

proceeded with the splitting: the first empirical evidence was that they did

not look surprised at all about how their teacher split them up and no one

complained. This might mean either that the split made sense to them or they

simply did not care or did not dare to speak out about their teacher’s

decision. Having interacted with the kids and having seen the teacher-students relationship

in the class, the first option looked more plausible to me.

Then we

gave time to the different teams to select a team name and logo and enjoy some

practical activity to create their task boards, pick a corner in the classroom

space, hang the whiteboard on the wall and craft their own team space.

The next

step was to stipulate an agreement on our routines.

When it

comes to decide the Sprint length and day/time for the different events, we had

some constraints:

- Marco works only 4 days a week in that class (school week in Italy is 6 days)

- We wanted the kids to work on the project mainly at school, not at home, so that we could observe and facilitate team dynamics

- I had mainly Friday and Saturday available to join them remotely over Skype

The

agreement came pretty constrained:

- Sprint length: 3 weeks

- Sprint Planning: Saturday mornings

- Sprint Review and Retrospective: Friday after lunch

- Daily Scrum: 8.45 in the morning (but 4 times a week, when my brother was in the class)

The

different teams worked on drafting their own team ground rules on a flip-chart,

which they then hung in their team space.

Last step

before moving to Sprint Planning was to draft the first version of Definition

of Done, which I renamed with the slogan “We will have done a good job, if…” to

translate in a more suitable language for 5th graders J

Here below is a picture of how one of the

team’s corner looked like at the time they were building it the first day.

We had

finally everything ready to get going with the first Sprint Planning.

My brother explained

the first few backlog items on top of the backlog, re-read and clarified the

Acceptance Criteria. He mentioned more than once that each team could pull any

backlog item they wanted in the order they were presented, but if they felt

that one item was too much to get done in 3 weeks, he was available to discuss

possible ways to split the work in smaller chunks.

No team actually considered this as necessary and on the other side no team believed they could take more than one

region into the Sprint. The whole class collaborated to agree which team pulled

which of the top 3 items in the backlog.

The teams

moved to decide on how the chosen work would get done.

I instructed them to split

the Backlog items in smaller tasks and the kids even started pulling tasks.

Each

student designed a magnet with his/her own avatar and put it close to a

post-it.

We encouraged pair working from the very beginning.

The day

ended with a celebration.

The kids

were extremely happy and enthusiast. Some of the comments I got from them included:

- “Will you stay with us for the whole school year?”

- “I usually have troubles in following, but today I understood everything”

- “We love you!” (This obviously moved me to tears!)

It looked

like we were on a good track and had managed to create the right foundations

for the experiment to give the expected results.

Side note:

the day after, I met the mother of one of the kids, which is a dear friend and

an ex-school mate of mine.

She stopped me and asked: “What the heck did you do

at school yesterday? My son came back so enthusiast like I have never seen him

before after a school day!”

I was in a

hurry: I simply smiled, hugged her and left. This event triggered the idea to involve the

parents as much as possible moving forward in the experience.

Stay tuned for the continuation of the story in a coming post!